Pidcock Powers to CX Title and Signals Superhuman Season

On the back of claiming the Cross World Championships, could cycling’s latest superstar now target the biggest one-day races on the road?

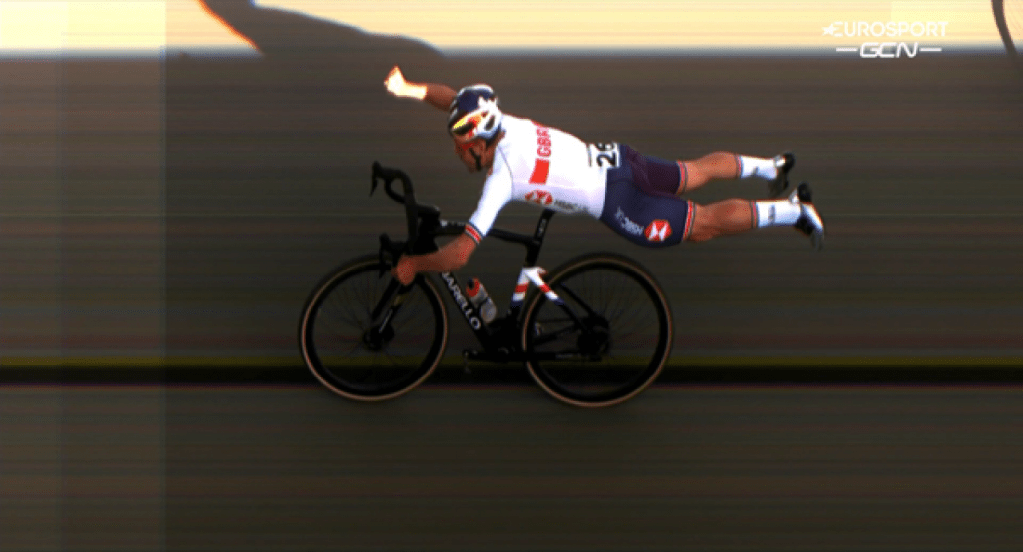

When Tom Pidcock crossed the line first in Fayetteville, Arkansas on Sunday to become the men’s world cyclocross champion, he confirmed his status as cycling’s latest superhero – and not just for the way he celebrated his victory.

By adding the rainbow stripes of world champion to his Olympic mountain biking gold, Pidcock has demonstrated superbly the talent he possess across multiple disciplines. A small, punchy rider who packs power beyond his frame, Pidcock has the potential to achieve just about anything in the sport.

Road cycling has already seen numerous elite talents cross over from CX in recent years, with Mathieu van der Poel and Wout van Aert being the standout names, but Pidcock has everything in his locker to compete with the titans of the sport for years to come.

And while MvdP and WvA may have been AWOL from Sunday’s race, Pidcock’s victory still came against a top-class field, all of whom were crushed by the Briton, unable to handle the ferocity of his attack with six laps remaining, and able only to follow his growing dust cloud carry away the top spot on the podium.

A prodigious talent from an early age, the 22-year-old from Leeds won the junior editions of world championships in cyclocross and road time trial as well as Paris-Roubaix, demonstrating his talent for the cobbles, something he may be hoping to repeat this spring.

He is now expected to line up in all the big one-day races in Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands in the first half of 2022, before featuring in Team Ineos’s eight-man squad for the Giro d’Italia in May for his first three-week Grand Tour.

Going into that hectic spring classics campaign, Pidcock will be confident of going head-to-head with the sport’s established big names, with van den Poel and van Aert joined by the likes of road World Champion Julian Alaphilippe, 2021 Tour of Flanders winner Kasper Asgreen and a man seeking to rediscover his mercurial best, Peter Sagan.

However, with just one win in the pro road ranks to his name, for Pidcock to instantly succeed in the biggest races would still be a surprise to many.

In a potentially strange twist of fate, a horrific crash and subsequent injuries suffered by Pidcock’s Ineos team-mate, Egan Bernal, could ultimately provide the Briton with a boost to his chances of springtime success.

While Pidcock was crushing his CX foes in Arkansas, 2,500 miles away in Bogotá, Colombia, Bernal was recovering from a shocking accident during a training ride that left him in need of multiple surgeries to his spine and, at one point, given a chance of less than 5% of recovering full mobility.

Clearly the priority for Bernal is making a full recovery from his injuries, which also include a broken thighbone and kneecap, before attention turns to his future cycling career. In the short term, his season is essentially over, meaning that Team Ineos will need to pivot their approach to the campaign.

Since arriving on the World Tour scene in 2010 as Team Sky, the outfit led by Sir Dave Brailsford have enjoyed massive success in the sport’s 21-stage Grand Tours, spearheaded by Tour de France wins for Bradley Wiggins, Chris Froome and Geraint Thomas as well as further success for Froome at the Vuelta a España and Giro d’Italia, where Tao Geoghan-Hart and Bernal have also taken the top step of the podium in 2020 and 2021 respectively.

However, in the big one-day races, the sport’s Monuments, Sky/Ineos have struggled to repeat that kind of success, with only two wins coming their way to date with victories for Wout Poels at Liège–Bastogne–Liège in 2016 and for Michał Kwiatkowski in 2017’s Milan-Sanremo.

Arguably, the team’s focus on winning the biggest stage races, including multiple training camps each season at altitude and ensuring their Grand Tour teams are packed with incredibly talented riders in service of their selected leaders, has potentially diminished their chances of winning more Monuments.

There have still been huge one-day wins for the team – particularly Kwiatkowski, with wins at E3 Harelbeke and Strade Bianche in addition to finishing first in Sanremo – but a squad of their depth and talent could and should have secured more consistent successes to their collective name.

Bernal’s injuries leave the team’s plans for the coming campaign in tatters, with no obvious replacement for the Colombian in terms of climbing ability or General Classification talent – while they might expect Thomas or Richard Carapaz to be able to step up, they surely are some distance from being able to challenge current double Tour de France winner Tadej Pogacar.

Which presents something of an opportunity for the squad to take a different approach and re-focus elsewhere in the season. When Geoghan-Hart won the Giro in 2020, it came as a surprise, clinched as it was on the final stage time trial into Milan. After the dust had settled and the Maglia Rosa awarded, Ineos boss Brailsford reflected on the way that race was won and how it could herald a new, attacking style of cycling for the team: “We’ve done the train. We’ve done the defensive style of riding and we’ve won a lot doing that,” he said, to velonews.com.

“But it’s not much fun, really, compared to this. What we’ve done here, the two Giros we’ve won. First with Froomey’s win on stage 19 [i.e. back in 2018] and the way all of the guys raced here, well, at the end of the day, the sport is about racing.

“It’s about emotion and the exhilaration of racing. And that’s what we want to be now.”

That new approach, taking races by the scruff of the neck, has yet to be seen unequivocally, despite Bernal’s success in the 2021 Giro where the Colombian was never really threatened after taking the pink jersey on stage nine and ultimately winning by a margin of 1’29” from Damiano Caruso.

With Bernal yet to begin his rehabilitation and recovery from breaking as many as 20 bones in his crash, Ineos could completely shift their approach to the 2022 season, throwing additional resource behind a committed bid for wins in Flanders or Roubaix.

Riders such as Kwiatkowski, Luke Rowe and Dylan van Baarle are outstanding competitors with immense pedigree, but who are often saved for deluxe domestique duties with training plans designed to peak around the Tour de France in July. Allowing them to ride off the leash could be a major headache for perennial classics big boys, Quick-Step Alpha Vinyl.

Combined with up-and-coming superstars like Pidcock, Italian powerhouse Filippo Ganna and reigning track Omnium world champion, Ethan Hayter, Ineos have the basis for team that could rival the best in the world.

While van der Pool continues to nurse a back injury from last season and van Aert potentially targets goals as far ahead as the Tour’s Green Jersey classification, this year could be the perfect opportunity for Pidcock to step into the vacuum created and grasp the opportunity it creates.

Targeting the sport’s biggest single-day events wouldn’t be easy as anything can happen on a single day, but with the way he demolished the opposition in Arkansas, cycling’s newest Man of Steel has proved that he has what it takes in the biggest races on the biggest stages.